Chinese Tea Cups: History, Types, Gongfu Rituals & Buying Guide

Small, handleless, often porcelain and quietly beautiful—Chinese tea cups look simple, but carry thousands of years of history, craft, and ritual in their thin walls. This guide walks you through where they came from, why they are so small, what makes a good cup, and how to choose the right one for your own tea table.

At a Glance: What Makes a Tea Cup “Chinese”?

A Chinese tea cup is usually defined by four features:

- Handleless design that keeps the hand close to the tea and the heat.

- Small capacity (often 20–60 ml for gongfu, 80–150 ml for casual use).

- Material and form tuned for aroma, temperature, and tea type (porcelain, clay, glass, etc.).

- Cultural symbolism in shapes, glazes, and patterns (lotus, dragon, crane, landscape, calligraphy).

Most modern Chinese tea cups fall into two big families: gaiwan (lidded bowl with saucer) and small open cups used in gongfu tea.

1. From Bronze Vessels to Porcelain Bowls: A Short History

Tea has been documented in China since at least the Han and became a refined art by the Tang (618–907 CE) and Song (960–1279 CE) dynasties. As tea evolved from medicinal decoction to whipped powder to loose-leaf infusions, the vessels evolved with it.

- Tang & Song: Thick, dark tea bowls (often Jian ware) suited powdered tea and dramatic foam.

- Ming & Qing: Loose-leaf infusion dominates; white and blue-and-white porcelain cups rise, prized for showing liquor color clearly.

- Modern gongfu: Small, handleless cups and the lidded gaiwan become standard, mirroring a shift toward repeated short infusions and mindful sipping.

Today, the classic image of a Chinese tea session is a low table, a small teapot or gaiwan, and several tiny cups being refilled again and again.

2. Why Are Chinese Tea Cups So Small?

If you are used to big Western mugs, Chinese tea cups can feel miniature. Their size is intentional, serving both practical and philosophical purposes.

2.1 Flavor and Temperature Control

- High leaf ratio, short brews in gongfu style create concentrated tea; small cups deliver just a few sips of this intense liquor.

- Small volumes cool quickly to drinkable temperature, so the tea is enjoyed at its peak instead of lukewarm.

- Repeated refills let you track how flavor changes across infusions, a key pleasure of good oolong, pu-erh, and other fine teas.

2.2 Social and Ritual Reasons

- Small cups encourage even sharing; the host divides each infusion among all guests.

- Frequent pouring creates natural pauses for conversation, gratitude, and observation.

- A modest cup reflects values of restraint and mindfulness—enough to savor, never to drown.

2.3 Aesthetic and Philosophical Layers

In Chinese aesthetics, beauty often lies in understatement. A small cup leaves space around it on the tray, highlighting proportion, negative space, and the way light hits the liquor. You are invited to pay attention to each sip instead of drinking on autopilot.

3. Main Types of Chinese Tea Cups

There is no single “official” Chinese tea cup. Instead, there is a family of forms, each tuned to a particular way of drinking tea.

3.1 Gaiwan (Lidded Cup with Saucer)

A gaiwan consists of three parts: bowl, lid, and saucer. You can brew tea directly in it and drink from the bowl, or pour into serving pitchers and cups.

- Typical size: 80–150 ml for solo or shared brewing.

- Materials: mostly porcelain, sometimes glass or clay.

- Best for: green tea, oolong, white tea, and any tea where you want to watch the leaves open.

The lid acts as both aroma cap and strainer; a skilled hand can pour a clean stream while holding back most of the leaves.

3.2 Gongfu Drinking Cups

These are the tiny open cups most people picture in a gongfu set.

- Capacity: roughly 20–60 ml each.

- Shapes: bell-shaped, tulip, straight-sided, lotus, flared rim, or low “saucer” style.

- Materials: porcelain, stoneware, Yixing clay, glass, or even silver-lined designs.

Their job is simple: deliver a small, beautiful portion of tea that cools quickly and shows color and texture clearly.

3.3 Aroma Cups (Wen Xiang Bei)

In some gongfu traditions, tea is first poured into a tall, narrow aroma cup, then decanted into a lower drinking cup.

- The empty aroma cup is brought to the nose to enjoy the lingering scent.

- This pairing emphasizes fragrance as a separate stage of the experience.

3.4 Regional and Specialty Cups

Beyond the core shapes, you’ll encounter:

- Jian-style bowls inspired by Song dynasty dark wares.

- Ru-style celadon cups with crackled, jade-like glaze.

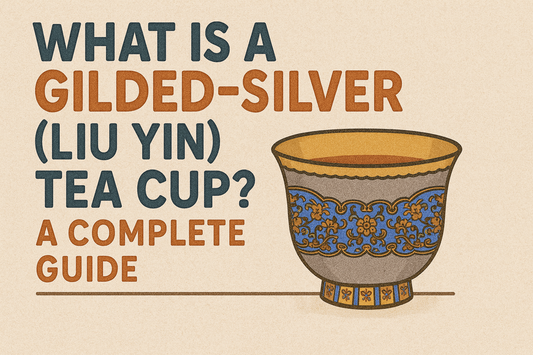

- Gilded-silver or silver-lined cups that reflect light dramatically.

- Lacquered or hand-painted cups reserved for special occasions.

Each form carries its own story and regional style; the right cup extends the character of the tea.

4. Common Materials and How They Change Your Tea

Material matters. It affects temperature, aroma, and how much the vessel interacts with the liquor.

4.1 Porcelain

- Neutral and honest: shows the tea’s true color and flavor.

- Good for: almost any tea, especially green, white, and delicate oolongs.

- Look for: thin, even walls and smooth glaze without rough spots at the lip.

4.2 Yixing Clay and Other Stoneware

- Porous and seasoning: gradually absorbs trace aromatics from tea.

- Good for: committed pairing with one category (e.g., roasted oolong, shu pu-erh).

- Note: not neutral—best for experienced drinkers who like a “house flavor”.

4.3 Glass

- Fully transparent: ideal when you want to watch the liquor’s clarity and color.

- Cools quickly: good for hot climates and casual sessions.

- Neutral taste, but less “soft” in the mouth than fine porcelain.

4.4 Metal and Hybrid Designs

- Silver or silver-lined cups: very conductive, bright reflections, luxury feel.

- Enamel & lacquer: decorative and symbolic, often reserved for special rituals.

For most people, a simple, well-made porcelain cup is the best starting point, with clay or special materials added later as your collection and curiosity grow.

5. How to Hold and Use a Chinese Tea Cup

5.1 Holding a Gongfu Cup

- Rest the cup on the pad of your middle finger, near the base.

- Use your thumb and index finger to gently pinch the rim, keeping grip light.

- Keep the remaining fingers relaxed; the hand shape itself becomes part of the aesthetic.

This grip keeps the cup steady without clenching, and lets you feel the warmth without burning your fingers.

5.2 Basic Serving Etiquette

- The host usually pours everyone’s cup before their own, and tops off as flavors evolve.

- Cups are normally filled to about 70–80% full, leaving space to swirl and smell.

- A gentle tap of the fingers on the table can signal thanks when someone pours for you.

5.3 Using a Gaiwan

When drinking directly from a gaiwan:

- Rest the saucer on your fingers, thumb stabilizing the rim of the bowl.

- Use the lid to hold back leaves, leaving a small opening to sip from.

- Take calm, small sips; this is not a vessel to gulp from.

6. How to Choose the Right Chinese Tea Cup for You

There is no universally “best” cup. There is only the cup that best matches your tea, your climate, your budget, and your rituals.

6.1 Start from Your Tea Habits

- Mostly drink green or white tea? Choose thin, light porcelain that shows color clearly.

- Love oolong or pu-erh gongfu sessions? Go for small 20–50 ml cups or a mid-sized gaiwan.

- Prefer single big mug sessions? A larger 100–150 ml Chinese cup can bridge styles.

6.2 Check the Shape

- Bell or tulip shapes concentrate aroma toward the nose.

- Wide, low cups highlight color and cool quickly.

- Slightly flared rims feel soft on the lips and frame the liquor beautifully.

6.3 Inspect Craftsmanship

- Look at the cup against light: walls should be even in thickness.

- Run a finger along the lip; it should be smooth, without sharp points.

- On painted or carved cups, designs should feel integrated, not like stickers or rough blobs.

6.4 Consider Symbolism and Emotion

The cup you reach for most often is rarely the most expensive one. It is usually the one whose motif and feeling speak to you:

- Lotus for purity and calm.

- Fish for flow and abundance.

- Bamboo, plum, pine for resilience and integrity.

Choose a design that makes you want to sit down and brew, even on a busy day.

7. Caring for Chinese Tea Cups

7.1 Daily Cleaning

- Rinse with warm water right after each session whenever possible.

- For porcelain and glass, a soft sponge and mild, unscented detergent are enough.

- Avoid heavy fragrances that can linger, especially inside small cups.

7.2 Stain and Odor Management

- Light tea film can be removed with a baking-soda paste or gentle citric acid soak.

- Do not use harsh abrasives that scratch glaze or cloud glass.

- Clay cups used for one type of tea are often not washed with soap at all—just rinsed and dried.

7.3 Storage

- Let cups air dry fully before stacking or boxing.

- Store in a low-humidity cupboard away from strong kitchen smells.

- Use dividers or cloth to prevent chipping if you stack multiple thin cups.

8. Chinese Tea Cups FAQ

Q1. Do I need a gaiwan to “properly” drink Chinese tea?

Not always. A gaiwan is a versatile tool and worth learning, but you can start with a small teapot and simple cups. What matters most is water, tea, and attention.

Q2. Can I use Chinese tea cups for coffee or other drinks?

You can, but be cautious with clay cups that absorb aroma. Porcelain and glass are more flexible; just remember that strong flavors may leave traces that change how later teas taste.

Q3. Are Chinese tea cups microwave and dishwasher safe?

Many modern porcelain and glass cups technically are, but delicate or hand-painted cups, gilded rims, and metal-lined designs are better washed by hand and kept out of microwaves to preserve detail and bonding layers.

Q4. Why do some sets include tall and short cups together?

The tall ones are usually aroma cups; you pour tea into them, then transfer it into the lower drinking cups. You smell from the tall cup, and drink from the short one, separating fragrance from taste.

Q5. How many cups should I get to start?

For a home gongfu setup, a practical starting set is: one gaiwan or small teapot, one fairness pitcher, and 2–4 cups. You can expand later with more shapes as you discover what you love.

Final Thoughts: Finding Your Own Cup

Chinese tea cups are small on purpose. They slow you down, ask you to notice the color of the liquor, the warmth in your fingers, the quiet between pours.

You do not need a museum-grade collection to begin. Start with one well-made cup that feels right in your hand. Brew a tea you already know and like. Watch how it looks in this new frame. Pay attention to what shifts and what stays the same. That attention is where the real taste of tea begins.

Elevate Your Tea Ritual

Discover the Silver Inlay Enamel Cup – Mandarin Duck & Peony Pattern.

A 40ml handcrafted porcelain silver teacup that blends timeless artistry with quiet elegance—crafted to enrich every mindful sip.